Henry Farrell characterizes the debate between Drezner and Slaughter as over "whether realism or networked internationalism best describes the basic contours of international politics" and thinks they're both wrong, preferring instead a view in which networks are important but that joint-gains functionalism is the wrong way to approach them: "If the kinds of international networked cooperation we see are all about struggles for resources, rather than achieving functionalist imperatives, then we may expect a very different international networked society than if these forms of cooperation are aimed at pursuing functionalist goals and Pareto-improvements". I read the debate, even more simply, as so:

Slaughter: Transnational networks are changing international politics by weakening or changing the role of the state, and this mostly leads to Pareto-improvements.

Drezner: Yeah, maybe, but states are still by far the most important actors in global politics and on many big-ticket items transnational advocacy networks have had little discernable effect. To the extent that non-state networks matter, it's largely because they change state preferences, not that they make states less relevant.

Farrell: Networks form for distributional reasons and states often cannot control them. In fact, states themselves are networks of politicians and bureaucrats. Networks transform politics via a complex process of contagion which is very difficult to predict ex ante.

Obviously some nuance is missing in these characterizations, but I think that's the gist of the argument. I have sympathy for all three views, but my own belief is that international politics operates somewhere in the space between Drezner and Farrell. That is, I think that networks play important roles in shaping international politics, but I think that their influence is best understood within the context of the state system. And despite the fact that international politics is comprised of a series of complex networks that interact, I don't necessarily think that "contagion" is the best way of thinking about these processes in all cases, nor that network behavior is a fundamentally mysterious phenomena.

Farrell and others cite the Arab Spring as a good contemporary example. According to

one view, the "Arab Spring" is a "black swan" -- a rare event that is essentially unpredictable. I think Farrell would modify the Blyth-Taleb story about probability distributions into a network context, where "black swans" are now viewed as shocks to networks that diffuse through the system in idiosyncratic ways. In some cases the network may be transparent enough that we can predict how extreme shocks might affect the network, but in other cases we won't have that information, and anyway we can't know when or how the shocks will occur. In this view the Arab Spring is a phenomena that cascaded across state borders in a way that states could not understand much less control. Factor in social media and other coordinating devices -- which are networks themselves -- and it gets messy very quickly.

But the alternative view of the Arab Spring, which I believe is more or less the dominant view of those who study contentious politics, is that diffusion dynamics themselves are not enough to explain when revolutions succeed or fail.* Quite often it is the decisions of centrally-located actors that play the most significant role. For example, the Egyptian revolution succeeded because the military chose to protect the protesters in Tahrir Square rather than killing them, and because key international allies pulled support from the Mubarak regime. The attempted revolution in Bahrain failed because the state, with support from foreign allies, was able to mobilize the military to put the insurrection down. This story isn't about cascading network spillovers infecting international politics in chaotic ways, but about the ability of governments to do what is necessary to keep elites on their side. In Libya, the revolution was likely to fail without international intervention. In Egypt, international intervention was almost non-existent. But in each case there are clearly-identifiable actors operating within the network that are having an important effect on outcomes. In at least some cases their behavior may be predictable by either interest-based or ideational approaches.

Perhaps most significantly, to my knowledge there is no evidence that the Arab Spring is an internationalist movement rather than a series of local movements that have arisen somewhat idiosyncratically. Networks played an important role in organizing protesters domestically, but there didn't seem to be any similar network coordinating actors at the regional level, and not all Arab countries have experienced prolonged protest periods. This is what I was referring to above when I said that contagion stories can only take us so far. A contagion story would have to be able to explain why protests spread from Tunisia to Egypt and elsewhere in 2011, but not from Iran in 2009. Or why protests spread from Tunisia to Egypt to Syria but not to Jordan or Lebanon. Or why reforms in Morocco appear to have been accepted by the populace, while they were rejected in Syria. In other words, there appears to be plenty of room for some sort of two-step analysis when determining how, when, and why social movements diffuse through the system.

Which actors are the most important may be a function of network characteristics, but quite often the relative importance of different actors

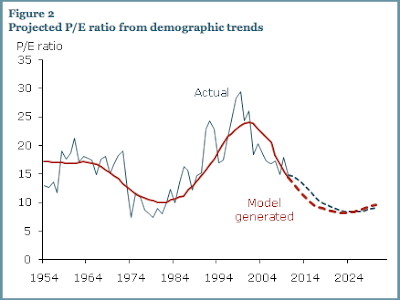

is knowable ex ante. As a critical central node in Egyptian society, no one was surprised when the defection of the Egyptian military tipped the scales in the revolutionaries' favor, and it seems that protesters believed early on that such a defection was likely if the crowds could sustain momentum for awhile. This belief provided just the motivation needed to sustain that momentum. Similarly, if we think about why the US financial crisis led to a global recession while the Swedish crisis in the 1990s did not, we can look to network characteristics of the global financial system and immediately see that the US is a much more important node than Sweden. We could then consult network theory that suggests that in highly unequal systems that are tightly inter-connected, networks are robust to shocks in the periphery but fragile to shocks in the core. Contra Farrell then, having a grasp of how networks behave and what the financial network looks like thus makes even complex phenomena like the financial crisis much

easier to understand.

So on a fundamental level I'd argue that Farrell's claim that the international political system is best understood as "space for contagion" is missing something, at least under most common definitions of network contagion which tend to influence structure over agency. For one thing, as an empirical matter

"contagion" often doesn't operate in ways we might expect. Revolutions are not viruses. Neither are neoliberal economic reforms or most other policies/outcomes that are often described in terms of diffusion or contagion. I'd rather say that we can use networks to understand the bargaining space within which strategic political actors interact. And if we understand how network dynamics confer power to some actors over others, then outcomes in international politics can be more easily understood.** The pattern of interdependence in networks is thus an important causal variable, but is not determinate on its own. Like Farrell (and Drezner), I do not assume that these interactions are necessarily Pareto-improving, or that they ordinarily will be. Unlike Farrell, I think that the role of states within these networks is likely to be substantial for all definitions of "state".***

Despite all of that, I think Farrell is much more right than wrong in emphasizing the ways in which networks affect international politics in ways not expected by most realist theory. And I think he's right to argue that Slaughter's focus on joint-gains functionalism is misplaced optimism in many cases. But I think the lesson from these corrections is not necessarily that international politics is a space for contagion to spread in unknowable ways, but rather that we need to situate political actors within a structural context to understand how they shape policy and respond to events.

*I'm heavily influenced in this by the research and teaching of UNC prof Graeme Robertson, who has written about and discussed the Arab Spring

here and

here. His

current research is on contentious politics in post-Communist states.

**For one example of this see Charli Carpenter's

recent IO article on gatekeepers in advocacy networks.

***In other words, depending on the analysis, we may need to complicate states along lines that Farrell suggests. Sometimes the subtle two-step that Drezner advocates will be fine. As Bear Braumoeller notes in comments to Farrell's post, endogeneity problems quickly emerge when you try to internalize everything into network analyses. Nevertheless Farrell is correct in saying that if we think of world politics as a complex adaptive system (and we should), then problems quickly emerge when we "black-box" any one level of analysis. Unfortunately there's no simple solution for this, but there are ways to gain tractability by shifting focus from one level of analysis to another without completely losing sight of the other levels.